It's been nearly half a year since the one time I saw ZDT. While I may be fuzzy on the details, I think the elapsed time enables me to speak clearly to the lasting impressions the movie leaves.

It's been nearly half a year since the one time I saw ZDT. While I may be fuzzy on the details, I think the elapsed time enables me to speak clearly to the lasting impressions the movie leaves. My friend Andrew Isker posted a comment on facebook the other day about the movie Zero Dark Thirty, which he then turned into a blog post over at Kuyperian Commentary . I disagree with his take on the movie, and so I promised him a longer response to his arguments than was possible in a facebook comment; this is that response.

I actually liked ZDT. I thought it was a well-crafted film, and I thought it was telling a good story. It's not an easy film, in any sense of the word. Andrew (who is also a co-worker and will be taking over the US History class I taught for two years) disagrees.

He makes four separate critiques, but they all center on what he sees as the movie's advocacy of torture. He says:

"Here we have torture graphically portrayed, but rather than revolting the viewer and forcing him to rethink his nation’s foreign policy objectives, it is portrayed as a necessary evil serving the interests of the foreverwar. Every time the portrayals of torture bring you to the point of being sickened, another terrorist attack will be re-enacted on screen to show you just how “worth it” torture is."In a comment, he added:

I’d like to believe that [getting Americans to think about torture differently] was what Bigelow was doing, but then why all of the re-enacted terror attacks? Why the voices of people dying in 9/11? If I’m going to make something to subliminally make people rethink their position on torture, doesn’t interspersing the primary justification for it throughout the movie defeat that purpose?

I'd like to respond on several fronts:

The movie did not actually advocate torture.

The director, Katherine Bigelow, said herself that "torture is reprehensible," and that she wished torture was not part of the history of the hunt for UBL. Her goal, she said, was to tell the story as accurately as possible within the constraints of a film (compressing ten years into two and a half hours), and that to leave out the torture would be to "whitewash" history.Now, it's possible for a director - even, or perhaps especially, a well-intentioned one - to fail. However much Katherine Bigelow wanted to avoid advocating torture, ZDT might push it in spite of her best efforts. That did not happen. There is only one scene I remember which could possibly be construed as a Rah-Rah-Torture dance, the one in which President Obama is shown denouncing torture while CIA agents gripe about how the new policies will make their jobs harder.

Interestingly, though, the movie actually goes on to answer these agents in two ways. First, we're shown that they gain a lot of useful information through other means: old-fashioned boots-on-the-ground investigation, bribes, and information that had been sitting around in their files since 2001. Second, we're shown that their jobs are already hard. Torture is not an "easy" way of gaining information. It takes a toll on the agents, one of whom gets out of field work specifically because he can't bring himself to torture guys anymore.

If you want to communicate truth to an audience, I tell my rhetoric students, you have to constantly think about who you are and who they are. If you are a decorated director and a darling of the "liberal media elite", you aren't in a great position to persuade a decidedly pro-enhanced-interrogation audience. You're the sort of person Rush Limbaugh serves for breakfast with a side of bacon. And so you need to be extra careful about avoiding straw men. You absolutely must not forget to answer their strongest argument.

If you want to communicate truth to an audience, I tell my rhetoric students, you have to constantly think about who you are and who they are. If you are a decorated director and a darling of the "liberal media elite", you aren't in a great position to persuade a decidedly pro-enhanced-interrogation audience. You're the sort of person Rush Limbaugh serves for breakfast with a side of bacon. And so you need to be extra careful about avoiding straw men. You absolutely must not forget to answer their strongest argument.

One of the most persuasive arguments, the one that grabs us by our revenge-gland and doesn't let go, is that "we used it, and we got bin Laden." Bigelow does her job by presenting that position clearly. At the same time, she undermines its strength through the rest of the movie.

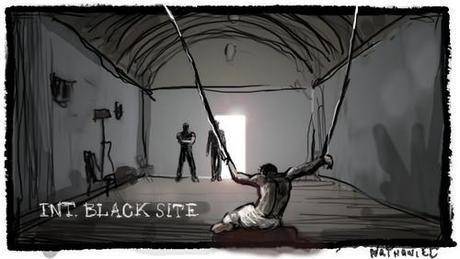

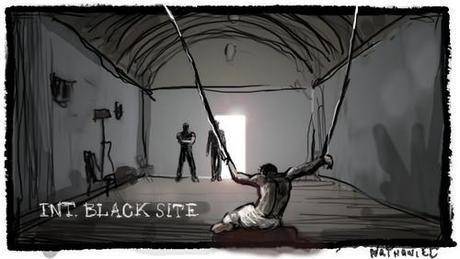

She removes the possibility of euphemism about "enhanced interrogation." You can't watch those first 45 minutes of the movie and come away with the idea that this is leaving a guy alone for an hour, with a bright light overhead, to sweat it out. This is pretty close to Marathon Man. As Andrew Sullivan said,

She also shows how torturing other human beings breaks even the likeable characters. Many people who support torture believe that the towel-heads have it coming; if you make the decision to become a terrorist, then you're gonna get what you deserve. The same people, however, don't think that our guys deserve to suffer. If you show them what it does to us, they just might feel prompted to re-think their view of torture generally.

Jessica Chastain brilliantly captured how Maya is hardened by her experiences with torture; it made her ruthless, but it also made her brittle and abrasive. The look she gives at the very end is so bleak, so shattered. Her obsession, and everything she did in pursuit of it, is written on her face. And it's not a look anybody in the audience wants to have.

The Gospel Coalition blog recently posted a list of was to "Discourage Artists in the Church." Three of the items on the list apply here:

If I actually believed that Zero Dark Thirty advocated torture, I would object to it in stronger terms than even Andrew has used. But, in fact, Zero Dark Thirty undermines the mindset that supports torture. It shows the costs; it shows the reality; it shows the alternatives. It can't avoid the real historical fact: we tortured terrorists, and that torture was part of the eventually successful hunt for Osama bin Laden. It can and does, however, show us how brutally ugly the whole story was and make us, like the director, wish it had been different.

Zero Dark Thirty undermines the idea of torture

If you want to communicate truth to an audience, I tell my rhetoric students, you have to constantly think about who you are and who they are. If you are a decorated director and a darling of the "liberal media elite", you aren't in a great position to persuade a decidedly pro-enhanced-interrogation audience. You're the sort of person Rush Limbaugh serves for breakfast with a side of bacon. And so you need to be extra careful about avoiding straw men. You absolutely must not forget to answer their strongest argument.

If you want to communicate truth to an audience, I tell my rhetoric students, you have to constantly think about who you are and who they are. If you are a decorated director and a darling of the "liberal media elite", you aren't in a great position to persuade a decidedly pro-enhanced-interrogation audience. You're the sort of person Rush Limbaugh serves for breakfast with a side of bacon. And so you need to be extra careful about avoiding straw men. You absolutely must not forget to answer their strongest argument.One of the most persuasive arguments, the one that grabs us by our revenge-gland and doesn't let go, is that "we used it, and we got bin Laden." Bigelow does her job by presenting that position clearly. At the same time, she undermines its strength through the rest of the movie.

She removes the possibility of euphemism about "enhanced interrogation." You can't watch those first 45 minutes of the movie and come away with the idea that this is leaving a guy alone for an hour, with a bright light overhead, to sweat it out. This is pretty close to Marathon Man. As Andrew Sullivan said,

"No one can look at those scenes and believe for a second that torture is not being committed. You could put the American in a Nazi uniform and the movie would be indistinguishable from any mainstream World War II movie. Yes, that's what we became in our treatment of prisoners."

She also shows how torturing other human beings breaks even the likeable characters. Many people who support torture believe that the towel-heads have it coming; if you make the decision to become a terrorist, then you're gonna get what you deserve. The same people, however, don't think that our guys deserve to suffer. If you show them what it does to us, they just might feel prompted to re-think their view of torture generally.

|

| This isn't even really "THE look", but it's close. |

Jessica Chastain brilliantly captured how Maya is hardened by her experiences with torture; it made her ruthless, but it also made her brittle and abrasive. The look she gives at the very end is so bleak, so shattered. Her obsession, and everything she did in pursuit of it, is written on her face. And it's not a look anybody in the audience wants to have.

Christian Art

I wrote a rant a while back about how a Christian should have made Slumdog Millionaire. It's not published (it was, after all, a rant) but the main point was that there are excellent movies being made by people who are willing to portray the world honestly while Christian artists make, pardon me, Fireproof.The Gospel Coalition blog recently posted a list of was to "Discourage Artists in the Church." Three of the items on the list apply here:

I would contend that demands like the ones Andrew has made implicitly, through his comparison to "Algiers", are part of the problem with Christian art. While I don't think Andrew would say this in so many words, his problem with ZDT flows out of the same mindset that says "Movies that portray sin need to always condemn it loudly and unambiguously."

- Treat the arts as a window dressing for the truth rather than a window into reality

- Only validate art that has a direct application

- Demand artists to give answers in their work, not raise questions ... Do not allow for ambiguity, or for varied responses to art. Demand art to communicate in the same way to everyone.

If I actually believed that Zero Dark Thirty advocated torture, I would object to it in stronger terms than even Andrew has used. But, in fact, Zero Dark Thirty undermines the mindset that supports torture. It shows the costs; it shows the reality; it shows the alternatives. It can't avoid the real historical fact: we tortured terrorists, and that torture was part of the eventually successful hunt for Osama bin Laden. It can and does, however, show us how brutally ugly the whole story was and make us, like the director, wish it had been different.

No comments:

Post a Comment